Do perceptions of risk in the construction industry correlate with fluctuations in green bond markets? In this study, Donglai Luo, RICS economist, explores the relationship between construction professional sentiment and sustainable finance markets.

Green bonds are important for sustainable financing but concerns over inconsistent ESG standards and lack of transparency persist. The RICS survey responses from the construction industry found that green bond issuance is suppressed in times of financial constraint, and there is a need for more transparent and consistent standards. Meanwhile, green bond performance in the secondary market appears to be positively influenced by increasing perceptions of climate risk among construction professionals.

Green bonds are one of the main instruments for sustainable financing. They are also used as a policy tool to encourage funding for projects that have positive environmental or climate change related impacts. However, in the past few years, there has been growing debate over the effectiveness of green bonds. On the one hand, an increasing number of projects declaring their ESG credentials are requiring funding. Growing interest in real estate green bonds is evident, for example, with the International Finance Corporation’s substantial investment in the South African real estate investment trust Redefine Properties' green bond in 2022. Last year also saw the launch of green bonds from Central Pattana Plc (CPN) and United Overseas Bank (UOB) in Thailand, designed to stimulate the growth of mixed-use and green buildings domestically and overseas.

“As a relatively new market with a lack of consistent standards or transparent monitoring and reporting, green bond markets can be said to have ‘embedded immaturity’.”

On the other hand, investors still harbour concerns about the efficacy of green bonds as a comparatively new asset class. The doubts mainly relate to two matters. Firstly, there is inconsistency in ESG standards between different projects, asset classes and countries, making it hard to compare investments. Secondly, a lack of transparency around how compliance with ESG standards is being enforced, putting the reputation of the investor (and issuer) at risk of accusations of green washing, and making the green bond vulnerable to market volatilities. For example, with the economic downturn and rising inflation, green bond issuance from China effectively shut down in 2022, with a significant portion of issuers in that sector in distressed financial condition.

As a relatively new market with a lack of consistent standards or transparent monitoring and reporting, green bond markets can be said to have ‘embedded immaturity’. It is crucial to understand how sentiment concerning global economic headwinds and indications of increasing climate change among those involved in the green bond issuer side (real estate and construction professionals) might impact the performance of green bonds in the market.

The relationship between professional sentiment and green bond issuance during an economic downturn

In the face of financial constraint, are green bonds being seen as an alternative means of funding? And if so, are issuers taking advantage of the lack of standards and enforcement to win this financing, i.e. by greenwashing?

One way to test this idea is to compare time series data indicating how much financial constraints have negatively impacted construction markets in the last three months (taken from the Quarterly RICS Global Construction Monitor (GCM)) with market data on bond issuance for the building sector (from Climate Bond Initiative).

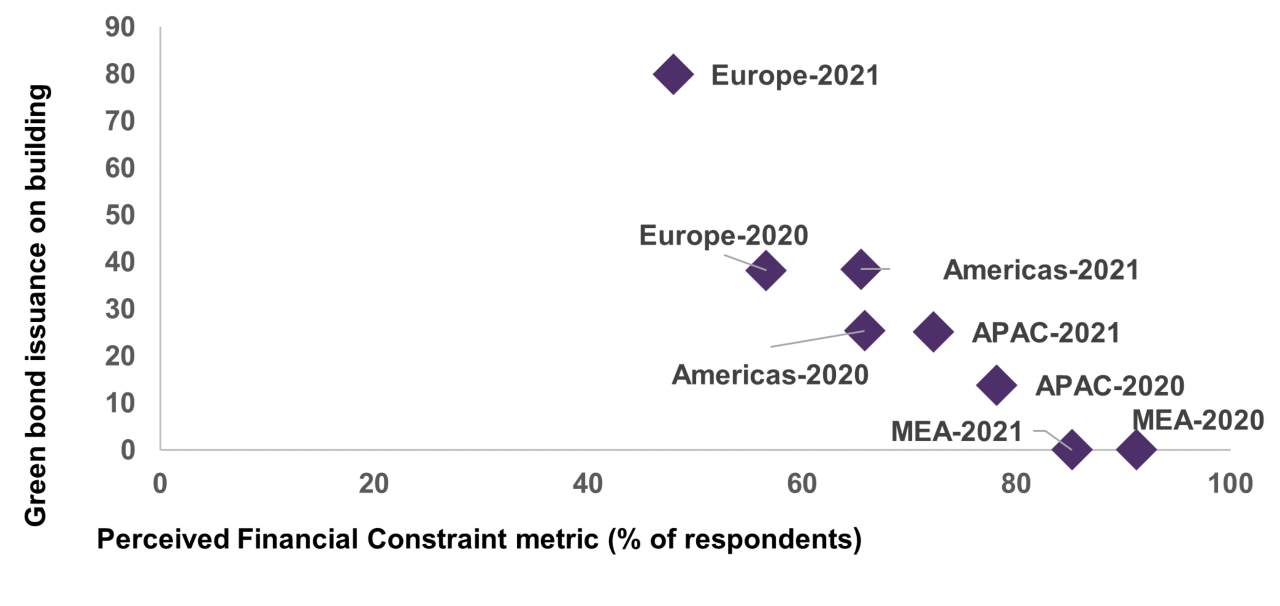

Figure 1: Perceived financial constraint metric (% of respondent) vs. green bond issuance value ($bn)

Sources: RICS GCM; Climate Bond Initiative

Figure 1 shows a clear linear relationship between the perceptions around financial constraints and green bond issuance. However, contrary to what might have been anticipated, the patterns in the past two years do not indicate that green bonds were used as a tool to circumvent the constraint on regular bond issuance. To the contrary, our results show an inverse relationship: there is no evidence to support our theory of greenwashing. In the quarters where perceived financial constraints in construction rose, green bond issuance actually fell.

Looking at this data on a region-by-region basis (Figure 2), the nascent green finance funding opportunity appears to have been better adopted in the more mature markets. In fact, the pattern coincides with the claim that green bonds are still very risky for investors. Therefore, issuance would be better received in more established markets.

A tentative conclusion to draw from this is that for market situations where the perceived financial constraint is significant in influencing behaviour, green bond issuance for the real estate sector is suppressed. This calls for more transparent and consistent standards to reassure investors in stability of the primary market.

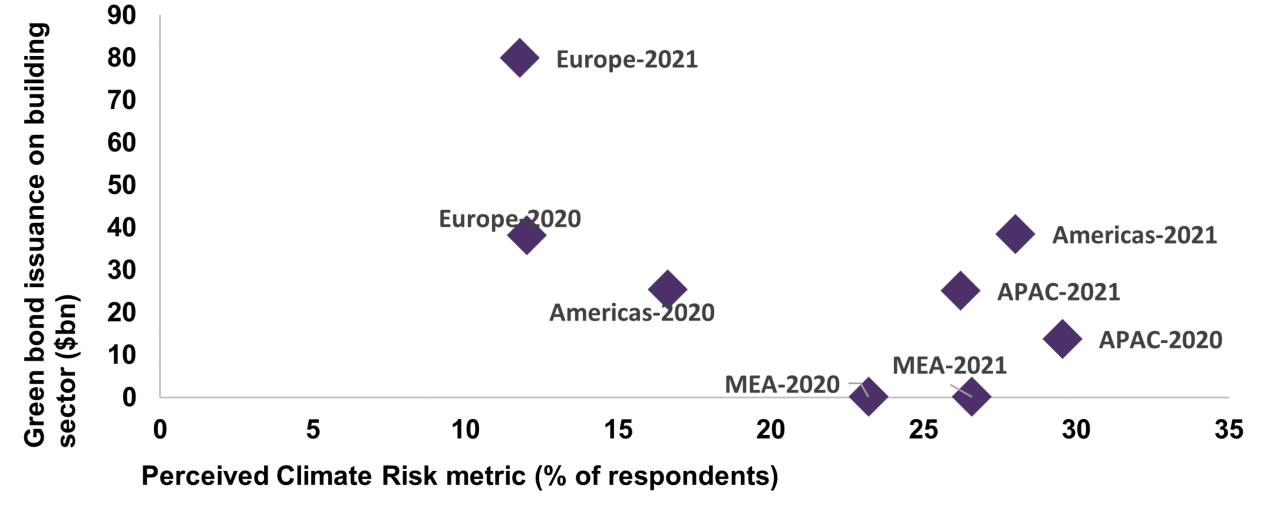

Figure 2: Perceived climate risk metric (% of respondent) vs. green bond issuance value ($bn)

Sources: RICS GCM; Climate Bond Initiative

A second approach we took was to compare time series data indicating how much climatic risks have negatively impacted construction markets in the last three months using the same CBI market data on bond issuance for the building sector. This yielded no correlation, and could suggest that climate risks, as perceived by construction professionals, does not affect the issuance of green bonds.

Government initiatives to support the growth of green bond markets in Asia Pacific

Since the first green bond was issued by the European Investment Bank in 2007, the global green bond market grew at an average annual growth rate of approximately 95%, with over US$ 2tn in green bonds issued globally to date. While this growth rate is considerable, a drastic upscaling of investment in green bonds is needed over the next decade and beyond, if countries are to meet their net zero commitments.

Despite the lack of consistency across different countries on what constitutes a green bond, global policymakers are designing new mechanisms to accelerate green finance. In Singapore, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has set up the sustainable bond grant scheme to help issuers reduce the incurred expense on external reviews and reporting (such as International Capital Market Association (ICMA) and Sustainalytics). At the same time, the Building and Construction Authority (BCA) in Singapore has launched the Green Building Masterplan, which vows ‘at least 80% of buildings (by floor area) in Singapore to be green by 2030’. The government has put efforts into encouraging the issuance of green bonds and is pushing for more projects in sustainable financing. The Singapore government has raised the mandatory environmental sustainability standards for new and existing buildings, including both the energy consumption and construction practice.

Many cities in China have also launched similar roadmaps, intended to assure investors and attract private investment. For example, Chongqing, a major city in southwest China, has set up targets of carbon neutrality for the years 2025, 2030 and 2060. Energy saving in construction industry has been emphasised as one of ten major tasks in the announcement by the municipality in April 2022. With these mandatory requirements, more construction projects will turn green, creating the need to issue more green bonds.

The relationship between professional sentiment and green bond market performance

Besides government initiatives to encourage green finance, the performance of the green bond assets in secondary markets – where bonds are bought and sold among investors – is also worth closer look. Given the relative immaturity of green bonds as a financial asset class, how reactive might investors be to factors that could negatively impact the productivity of projects and/or companies funded by green bonds? And is there any evidence that the price of green bonds in secondary markets correlates with sentiment about perceived risks from professionals working on the issuer side (in construction and real estate)?

Using China as an example, we ran a baseline regression, comparing green bond returns over the last ten years (using the China policy bank ten-year green enhanced bond total return index (source: macrobond)) against (1) time series data indicating how much financial constraints have negatively impacted construction markets in the last three months in China, and (2) time series data indicating how much climate risks have negatively impacted construction markets in the last three months in China (both taken from the Quarterly RICS GCM). The regression also includes the ten-year government bond rate as the control variable, which acts as the market rate benchmark. We use this to test if the perceived risks from the professional side have been priced in.

The results (Table 1) suggest promising correlation. In contrast with the insignificant effect of the climate risk perception on the issuance, the performance of green bonds in the financial market shows a statistically significant correlation to professional perceptions that climate risk has negatively impacted construction. In other words, returns on green bonds are likely to increase as construction sector sentiment that climate risks are negatively impacting construction markets increases.

“Returns on green bonds are likely to increase as construction sector sentiment that climate risks are negatively impacting construction markets increases.”

A tentative conclusion to draw from this research is that increasing perceptions of climate risk among those working in construction appear to have a positive influence on green bond performance. One possible explanation for this correlation would be the weather anomaly perceived by the respondents is also perceived by the market participants. Another would be that the secondary market in green bonds can digest climate risk better than the new issue market.

Table 1: Regression results

Perceived climate risk |

Perceived financial constraint |

|

Coefficient |

0.171* |

0.102 |

Std. error |

(0.088) |

(0.107) |

Control variable: |

10-year gov. bond rate |

10-year gov. bond rate |

Adj. R2 |

0.754 |

0.704 |

Note: *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

Data sources and limitations

For the interests of this article, we have drawn upon the Quarterly RICS Global Construction Monitor (GCM), making certain assumptions about the reasoning behind participant’s responses.

Specifically, we looked at the question ‘Have any of the following factors negatively impacted activity over the past three months?’ and selected responses where the participant answers included both ‘weather’ and ‘financial constraints’ among a range of other options.

We calculated the percentage of the respondents reporting each choice at the country level, and then grouped these into four world regional groups: the Americas, APAC, Europe and MEA. We interpret this percentage, or ratio, as the level of perceived risk for climate and for financial conditions. Using data gathered between 2020 and 2021, we built a time series of market sentiment around these two factors. This time series was the basis for comparison in the investigations mentioned above.

One limitation is the assumption around the selection of ‘weather’ as a factor being an indication of climate change. A respondent selecting the ‘weather’ as a factor could represent normal seasonal patterns rather than unusual climate events. Respondents may not relate the weather to the climate change. However, for the purposes of this research, we are assuming that a) respondents choosing weather does imply unexpected weather event, and b) these unexpected weather events are correlated with climate change. Another limitation stems from the frequency of available data. RICS survey data is updated on a quarterly basis, while green bond issuance data is only available annually. To gain a more precise understanding of the patterns, more granular data is required.

When examining the inverse relationship between perceived financial constraints and green bond issuance, one challenge to our interpretation would be that the greenwashing activities may be masked by the aggregation of annual and regional data. To investigate this issue, more detailed data on the green bond issuance is necessary for future research.

Contribute to the RICS Global Construction Monitor survey

Our professionals' input makes RICS surveys leading indicators in the industry. Taking part is quick and simple, and you receive full accreditation in our reports.

Completing each survey and reading the report can count as 30 minutes of informal CPD; regular participation can add up to 6 hours of informal CPD each calendar year.