Like many cities around the world, Singapore faces urban challenges including an ageing population, the need to renew infrastructure, climate change, while being a small and densely populated city-state with a lack of natural resources.

To find out more about how these challenges are being overcome, RICS recently caught up with Hugh Lim, Executive Director at the Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC), to explore Singapore’s approaches in shaping a resilient, liveable city that balances economic growth and sustainability targets.

Tell us about the Centre for Liveable Cities, Singapore

The Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC) was formed in 2008 out of a recognition that lessons and experiences from Singapore’s development journey may be of value to many cities, seeking to be both liveable and sustainable. By then, Singapore had come through several decades of intensive urbanisation, overcoming challenges like overcrowding and unemployment to become a thriving global city and an endearing home, despite seeing its population more than double over the period. CLC’s early work focused on capturing the learning points from this transformation and the tacit knowledge from our urban pioneers. The findings are reflected in our Urban Systems Studies series (which currently has 37 editions available online.) and serve as useful references in training programmes for city leaders and public officials.

Beyond documenting Singapore’s urbanisation journey, CLC today conducts forward-looking urban policy research, in areas such as sustainable mobility, urban liveability and regenerative design, in anticipation of future urban challenges, gleaning lessons from cities around the world.

CLC works with partners around the world, in the public, private and people sector, including many international organisations such as UN Habitat, C40 and the Resilient Cities Network. Our programmes and signature platforms, which include the World Cities Summit, reach out to city leaders from across the globe, in recognition of the value of knowledge sharing amongst cities and urban practitioners.

What makes a liveable city? Tell us about the challenges of making cities more liveable somewhere like Singapore?

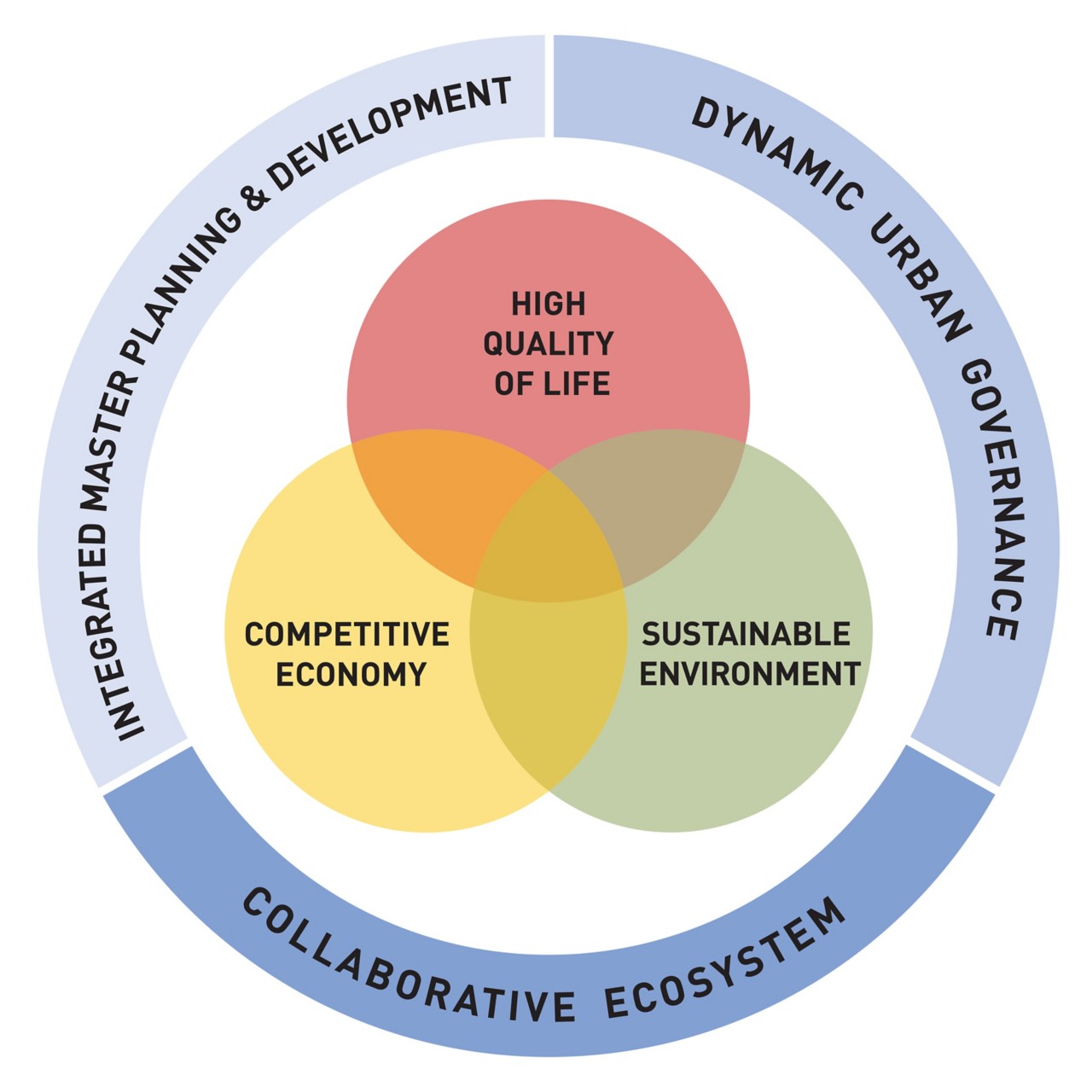

Drawing from the experience of Singapore and other cities, and taking into consideration emerging urban challenges, CLC developed the Liveability Framework (LF) which expresses three key outcomes that define Liveability: a competitive economy, a sustainable environment and a high quality of life.

A competitive economy provides jobs for a city’s residents and should encompass elements like dynamism and innovation. A sustainable environment goes beyond environmental protection and resource security to include building with nature and bolstering climate resilience. A high quality of life addresses fundamentals like affordable housing, safety and security, and, as cities evolve, includes sports, the arts and culture, mental well-being, social cohesion and a sense of belonging.

As a city-state with limited space, Singapore has to provide for these demands in a much more compact setting. We also have to allocate land for national needs like defense, international connectivity, energy and waste management, which are often sited outside of a typical city’s boundaries. Hence, Singapore has had to take a long-term approach in its urban planning to ensure that we safeguard adequate land for future generations to come.

Looking ahead, our city must cater for an evolving economy, an ageing society and new risks and imperatives arising from climate change. But these are also the kind of challenges faced by many cities worldwide. The question for us is how to turn our density into an advantage, for example, using it to provide efficient and convenient access to jobs and services in a polycentric urban structure, or achieving multi-functions in all our major infrastructure efforts, such as the “Long Island” project to guard against sea level rise, or warding off the worst urban heat island effects by incorporating nature and greenery in our neighbourhoods. A liveable city is not only able to juggle between trade-offs in policy and decision-making but also take active steps to harness synergies across different domains for high-impact and long-term outcomes that will benefit future generations.

How is Singapore balancing attempts to increase liveability, while at the same time creating a city that is resilient and economically competitive?

A widely accepted view of a resilient city is one that has the capacity to deal with shocks or crises, and able to adapt responsively and emerge stronger from them.

It’s important that cities incorporate resilience across the different outcomes of liveability, whether in fostering economic resilience to adapt to a more volatile world, enhancing physical and resource resilience against the effects of climate change, as well as nurturing community resilience through social capital and cohesion.

The LF outlines three systems that support cities in achieving and sustaining the liveability outcomes: integrated master planning and development, dynamic urban governance and the new addition – collaborative ecosystem. The first two systems are foundational to sustainable urban development but for larger, more complex cities facing new challenges, city governments must work with the community, private sector and regional or international partners. By embracing this approach to the development of our cities, we can strengthen both liveability and resilience.

These systems work in parallel to enhance urban resilience. A city needs robust institutions with the capacity to respond to ‘black swan’ events, as well as gradual changes over time through long-term planning and innovation. Moreover, the capacity to respond does not lie solely with the government but will require the collective stewardship and expertise of the public, private and people sector.

Can you tell us a little bit about some of the initiatives/projects being undertaken to increase liveability and improve sustainability?

Singapore has an ageing population, due in part to greater longevity, but also declining birth rates. Along with longer lifespans, we expect to see more persons living with dementia in the future. To prepare for this, CLC co-led the Dementia-Friendly Neighbourhoods (DFN) Study, together with the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) and the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD).

The study entailed gathering first-hand feedback from over 100 persons living with dementia, caregivers, and residents through observation, workshops and pop-up engagement sessions. This allowed us to have deeper insights into the needs of this particular and growing community. The findings led to the design of several DFN-inclusive infrastructure like sensorial gardens as well as design guidelines for others looking to expand on this initiative. This project demonstrates the value of a collaborative ecosystem in tackling a complex challenge, requiring the efforts of different stakeholders working together towards a common goal to achieve better outcomes.

We are also taking a long-term approach to preparing for climate change and its effects. In response to rising sea levels, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) is studying “Long Island” as a solution where we reclaim about 800 hectares of land off the East Coast to create “islands” that not only build resilience to sea level rise and flood risks but also provide more space for uses like parks and recreation. There have been comprehensive stakeholder consultations for this initiative. CLC was involved in this process and supported agencies like the URA, PUB and NParks in the facilitation of community engagement for the plans.

How is Singapore measuring and evaluating success in creating a liveable, that meets the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals and Singapore's commitment to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050?

The Singapore Green Plan 2030 was developed to align all of Singapore in meeting our net zero emissions by 2050, acting as a horizontal that coordinates between different policies across government. The Green Plan is underpinned by five pillars: City in Nature, Energy Reset, Sustainable Living, Green Economy and Resilient Future. In addition, the Plan enables us to play our part in the global effort against climate change, supporting the Paris Agreement as well as the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Green Plan outlines ambitious targets for Singapore’s sustainable urban development, with concrete timelines to drive momentum and track progress. For example, under the Energy Reset pillar, the Green Plan aims to complete 1.5 gigawatt-peak (GWp) of solar energy deployment to meet the annual electricity needs of about 260,000 households and 200 megawatt-hour of Energy Storage Systems by 2025. Notably, the latter was achieved ahead of schedule in December 2022. Looking ahead, the 2030 target is to grow the solar energy deployment to 2 GWp, to further advance our urgent need for renewable energy.

For the city as a whole, Singapore also produces a biennial Singapore Public Sector Outcomes Review (SPOR) to track key indicators for liveability. In the 2024 edition, this was reflected across four themes:

- Opportunities for All, at Every Stage of Life

- Quality and Sustainable Living

- Our Shared Future and Place in the World

- Strong and Resilient Economy

Our public agencies all identify and provide data representing relevant indicators, both to track achievements as well as areas for improvement. This ensures transparency and keeps the government on track in delivering its goals.

What are the tensions or challenges of balancing immediate and future/longer-term priorities and how are they being addressed?

Singapore uses its Long-Term Plan to steer land allocation to meet different purposes over a 50-year horizon, including housing, industry, transport, recreation and nature. The Master Plan then translates these broad strategies into specific land use and density for each parcel of land. Both plans are reviewed regularly on a ten- and five-year basis respectively, allowing the government to stay up to date with changing needs.

This mechanism has served Singapore well over the past decades, but with a more unpredictable world ahead of us, there is a greater impetus for agility and flexibility in our plans. For instance, urban planners are employing scenario-based planning to account for a range of possible outcomes and incorporating this into the review process for the Long-Term Plan. This also comprises identifying signposts that can alert us early about emerging trends and signal when plans may need to be recalibrated. On top of having a flexible mindset, it is crucial that we stay attuned to concerns and feedback from the ground. For the Draft Master Plan 2025, our urban planning agency, the URA has held exhibitions that address themes like well-being and health, e-commerce and recreation and how they would affect the built environment around us. Ideas and concerns surfaced by the public continue to shape plans before they are finalised.

As other cities strive to become more liveable, sustainable and resilient, what can these cities learn from the way Singapore has approached liveability, sustainability and resilience?

We hope that the LF provides city leaders and policymakers with a forward-looking and systems-focused approach to creating liveable and sustainable cities. While the LF is not a silver bullet to solve all urban issues, its structured approach may prove useful to other cities grappling with similar challenges.

It is through mutual knowledge exchange that we can collectively learn and strive towards achieving better liveability for our residents. In this regard, the World Cities Summit serves as a platform for city leaders and practitioners to discuss common challenges and how some cities have overcome them. During the 2024 edition, we hosted 3,500 delegates from close to 100 cities, underscoring its importance as a platform for city stakeholders to convene, connect and collaborate.

At the World Cities Summit 2024, CLC and the URA jointly launched the City Network for the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize (LKYWCP Network). The Network is a platform to widen the sharing of knowledge by leading cities, and to strengthen ties between cities in the network. It, thus, engenders a stronger culture of global partnerships and collaboration.